Updates, deletes, and reindexing

Keeping knowledge current requires more than "ingest once"—plan for churn.

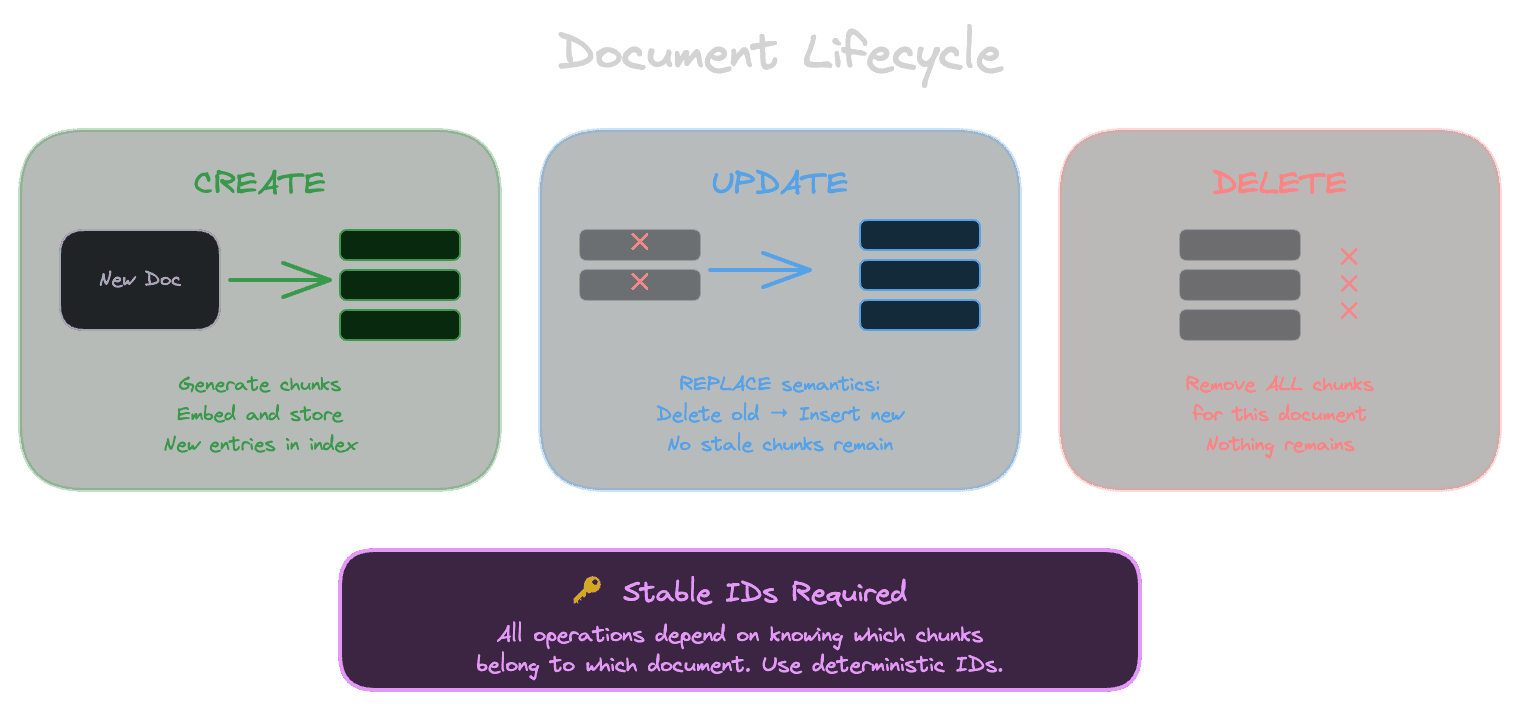

A knowledge base isn't static. Documents change. Pages get updated. Articles are corrected. Some content is deleted entirely—removed from the source, retracted, or aged out. If your ingestion pipeline only handles creation, your index will drift further from reality with every passing day.

This chapter covers the operations that keep your knowledge base current: handling updates, implementing deletes, and knowing when to reindex everything.

Update semantics: replace versus patch

When a document changes, you have two options for updating its chunks.

Replace semantics means deleting all existing chunks from the document and inserting the new ones. This is simpler and safer. You don't need to figure out which chunks changed; you just replace everything. If the document now produces fewer chunks, the extras are gone. If it produces different chunks, they're correct.

Patch semantics means identifying which chunks changed and updating only those. This is more efficient for large documents with small changes—you're not reembedding content that didn't change. But it's more complex: you need to detect which chunks are new, which are modified, and which are deleted.

For most systems, replace semantics is the right choice. The simplicity outweighs the efficiency cost. Unless you have very large documents with very frequent small changes, the extra embedding calls from replace-all aren't a significant burden.

Implementing reliable deletes

Deletion is the operation teams most often forget, and it causes real problems.

Why deletes matter. If a document is removed from your source—a page is unpublished, a ticket is deleted, a file is removed—and you don't remove its chunks from the index, retrieval will still return them. Users might see answers citing sources that no longer exist. Worse, they might see information that was deliberately removed: corrected errors, redacted content, or material that should have been deleted for legal reasons.

Detecting deletions. The challenge is knowing when something was deleted. Your source might not notify you; you have to detect the absence. Common approaches include:

Fetching the complete list of documents from the source and comparing to what's in your index. Anything in the index but not in the source is a candidate for deletion. This works for batch pipelines but requires the source to support listing all documents.

Reacting to delete events from the source, if the source provides webhooks or change feeds. This is faster but depends on reliable event delivery.

Timestamping chunks with when they were last seen in the source. If a chunk hasn't been seen across multiple sync cycles, it's probably deleted. This is a softer delete that tolerates temporary source issues.

Delete guarantees. Be clear about what deletion means in your system. Is it immediate removal or eventual removal? Is it reversible? Do you keep audit logs of what was deleted? For compliance-sensitive content, you might need hard delete guarantees with audit trails.

Handling content that moves

Content sometimes moves without being deleted: a page URL changes, a file is renamed, a document is reorganized. From your pipeline's perspective, this looks like a delete (the old location is gone) plus a create (the new location appears).

If you detect the move, you can update the chunk IDs and provenance metadata to reflect the new location without regenerating embeddings. If you don't detect it, you'll delete the old chunks and create new ones, which is wasteful but correct.

Move detection requires the source to tell you about moves or to provide stable identifiers that don't depend on location. A CMS that assigns each page a UUID independent of its URL path makes moves easy to handle. A file system where you identify documents by path makes moves look like delete-plus-create.

For most systems, treating moves as delete-plus-create is acceptable. The cost is reembedding content that didn't change, not correctness.

When to reindex everything

Sometimes you need to reprocess all content, not just what changed. The triggers include:

Changing your chunking strategy. If you adjust chunk size, overlap, or boundaries, existing chunks are based on the old strategy. To see the benefit of the new strategy, you need to rechunk everything.

Changing your embedding model. Different embedding models produce different vectors. If you switch models, existing embeddings are in the wrong space—queries will use the new model, but documents are embedded with the old one. Reembed everything.

Changing your cleaning or normalization. If you modify how content is cleaned before chunking, existing chunks have the old cleaning applied. Reprocess to apply the new rules.

Discovering a bug. If you find that your pipeline was mishandling certain content (wrong encoding, missed extractions, broken chunking for a specific format), you need to reprocess affected content.

Reconciliation. Periodically reprocessing everything from source—even without changes—catches anything the incremental pipeline missed. This is a safety net, not a replacement for good incremental handling.

Managing reindexing at scale

Reindexing everything sounds simple, but at scale it's an operation that requires planning.

Time and cost. If you have a million chunks and each requires an embedding call, that's a million API calls. At typical rates, that might take hours and cost meaningful money. Know your scale and budget accordingly.

Minimizing impact. Reindexing generates load on your embedding provider and your database. Run during off-peak times if possible. Throttle to avoid hitting rate limits. Consider processing in priority order (most-queried content first) so the most important material is updated early.

Zero-downtime strategies. You might not want to update in place if it means temporarily inconsistent results. An alternative is building a new index in parallel, then swapping. This requires more storage but ensures users always see consistent results.

Validation. After reindexing, validate that results are correct. Run your evaluation suite. Spot-check retrievals for important queries. A reindexing bug at scale can degrade your entire system.

Building for churn

The underlying mindset is that content churn is normal, not exceptional. Your pipeline should be designed around it.

Make updates and deletes first-class operations, not afterthoughts. Test them regularly—including delete-everything-and-reindex—so you know they work when you need them. Monitor for orphaned chunks (content in the index without a corresponding source) and stale content (long time since last update).

The goal is a knowledge base that tracks its sources reliably, so users can trust that the information is current.

Next

With lifecycle operations understood, the final chapter of this module covers the practical side of ingestion: costs and throughput.