Structure-aware chunking

Preserve meaning by respecting headings, lists, code blocks, and table structure.

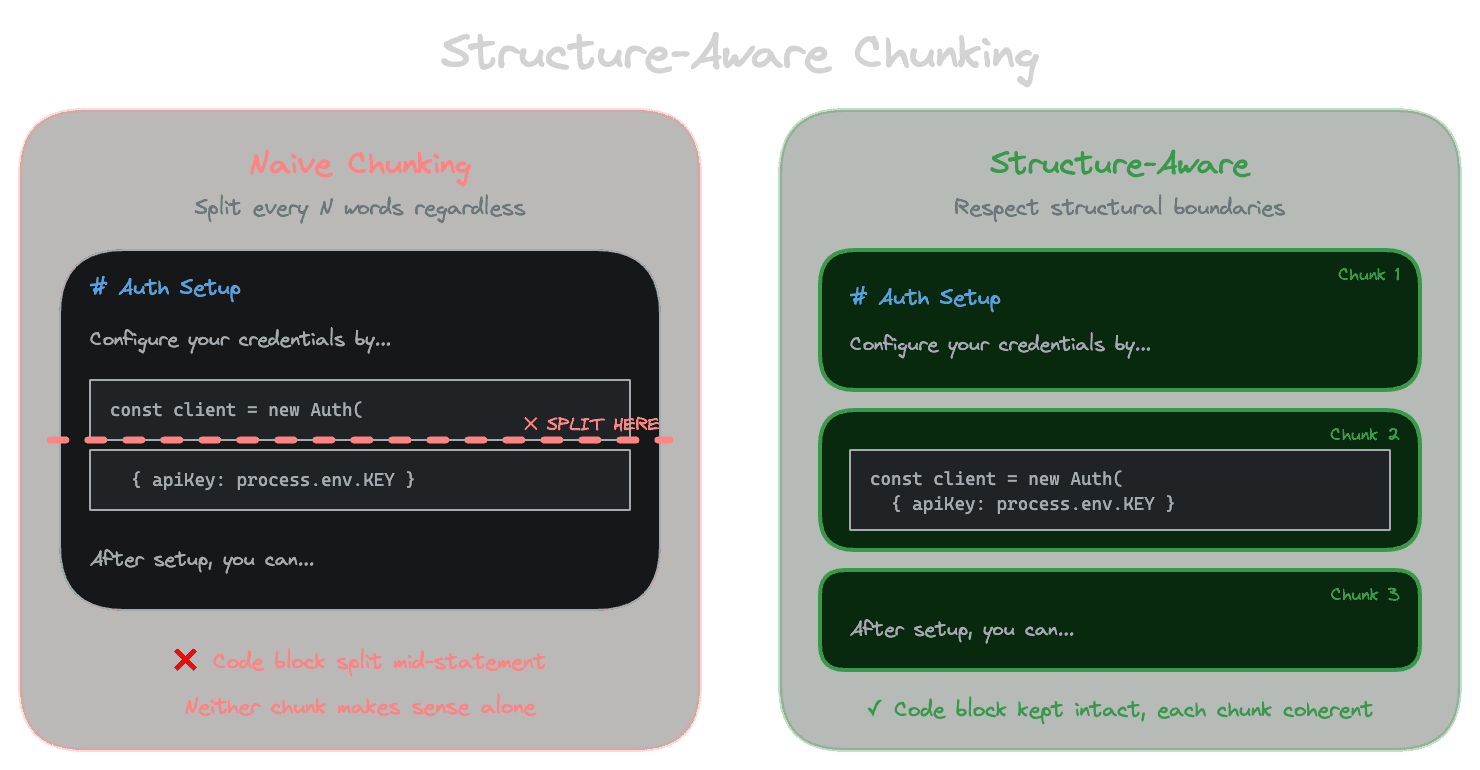

Naive chunking treats documents as flat streams of text, splitting every N words without regard for what those words mean. Real documents have structure: headings that introduce topics, code blocks that should stay intact, tables where rows and headers belong together, lists that enumerate related items. Structure-aware chunking respects these boundaries, producing chunks that preserve meaning rather than fragmenting it.

Why structure matters

When you split a document in the middle of a code example, neither resulting chunk makes sense on its own. The first half has variable declarations without the logic that uses them; the second half has logic without context. An embedding of either chunk poorly represents what the code does, and an LLM trying to use either chunk as context will struggle.

The same applies to tables. If you split a table between rows, the second chunk loses the header row that explains what each column means. A chunk containing "3.2%, $1,500, false" is useless without knowing those are the discount rate, minimum order, and eligibility flag.

Lists, too, suffer from naive splitting. A chunk ending with "The supported formats are: JSON, XML," and another starting with "CSV, and Parquet" each capture only part of the information.

Structure-aware chunking identifies these elements and adjusts chunk boundaries to keep them intact.

Chunking markdown and structured prose

Markdown documents have explicit structure: headings, bullet points, code fences, blockquotes. A structure-aware chunker for markdown typically follows these principles.

Heading boundaries are natural split points. Start a new chunk at each heading of a certain level (like h2 or h3). This ensures each chunk corresponds to a logical section of the document.

Never split within code blocks. When you encounter a fenced code block, keep it intact in a single chunk, even if that makes the chunk larger than your target size. Code blocks are atomic units of meaning.

Preserve lists as units when reasonable. A short list should stay together. A very long list might need splitting, but split between items, not within them.

Include context from parent headings. When a chunk represents a subsection, consider prepending the parent heading(s) so the chunk is self-describing. A chunk about "Error Handling" under a section about "Authentication" might be titled "Authentication > Error Handling" to provide context.

The exact implementation varies, but the principle is consistent: use structure to guide where splits happen rather than ignoring it.

Chunking code

Code requires specialized handling because its structure is syntactic, not just visual.

Function and class boundaries matter. A function is a semantic unit. Split between functions, not within them. If a function is very long, consider whether it should be one chunk or whether internal structure (like nested functions or major blocks) provides split points.

Keep related definitions together. A type definition and the function that uses it might need to be in the same chunk for the chunk to be useful.

File-level context helps. Prepend the file path to each chunk so the LLM knows where the code lives. Include imports or key context from the file header if they're needed to understand the chunk.

Language-aware parsing helps. A chunker that understands Python's indentation or JavaScript's braces can make smarter decisions than one that only sees characters. If your content is primarily code, invest in language-specific chunking.

For codebases, you might chunk at multiple levels: file summaries, function-level chunks, and perhaps line-level context for very specific retrieval. We'll cover multi-representation approaches later in this module.

Chunking tables

Tables are a special challenge because they're inherently two-dimensional, but embeddings and LLM prompts are one-dimensional text.

Option 1: Keep tables intact. If a table is small enough to fit in a chunk, keep it whole. Include surrounding context that explains what the table represents.

Option 2: Chunk by row with headers. For larger tables, each row (or group of rows) becomes a chunk, but prepend the header row to each chunk. The chunk "| Feature | Description | Price | ... | Premium widgets | Extended features | $99 |" makes sense; "| Premium widgets | Extended features | $99 |" alone doesn't.

Option 3: Flatten to prose. Convert table rows to sentences: "Premium widgets: Extended features, priced at $99." This loses the visual structure but makes each row self-contained.

The right approach depends on how tables are used in your content and how users query them.

Handling nested structures

Real documents have nested structure: a heading contains paragraphs, which contain lists, which contain items with inline code. Respecting all levels of structure while keeping chunks to reasonable sizes requires choices.

A common approach is hierarchical: major section boundaries (h2 headings) always start new chunks; minor structures (paragraphs, lists) are kept intact when possible but can be split if necessary; atomic elements (code blocks, table rows with headers) are never split.

Think about which structural elements are most important for meaning in your content, and prioritize keeping those intact.

When structure-aware chunking is worth the complexity

Structure-aware chunking is more complex than naive chunking. You need to parse the content format, identify structural elements, and implement logic to handle each type. Is it worth it?

For content with strong structure that's essential to meaning—code, technical documentation, data-heavy pages—structure-aware chunking usually pays off in retrieval quality.

For content that's mostly flowing prose without code or tables—blog posts, narrative articles—the gains are smaller. Sentence-aware chunking (just don't split mid-sentence) might be enough.

Test with your actual content. If naive chunking is producing chunks that don't make sense on their own, structure-aware chunking is likely to help.

Next

With structure covered, the next chapter examines token-based sizing: why word counts are a proxy for what actually matters, and how to chunk based on token limits.