Embeddings and semantic search

How text becomes vectors, what similarity means, and why semantic retrieval fails in predictable ways.

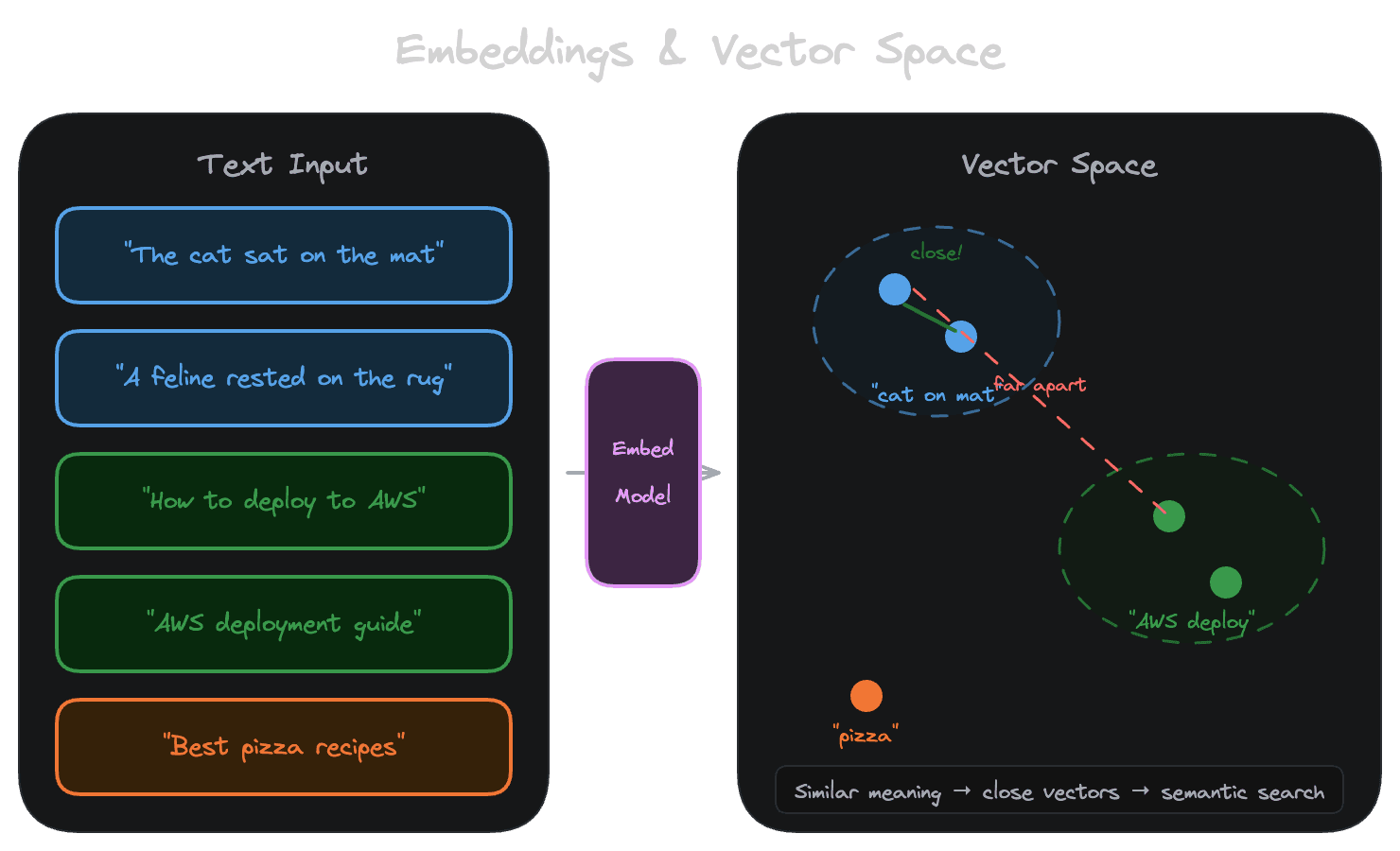

Embeddings are the foundation of modern retrieval. They let you search by meaning rather than keywords, finding content that's semantically similar to a query even when the exact words don't match. Understanding what embeddings actually do—and what they don't—helps you build systems that work and debug them when they don't.

What embeddings are

An embedding is a vector: an array of numbers (typically 384 to 3072 floats) that represents a piece of text. The embedding model learns to place similar texts near each other in this high-dimensional space. "How do I reset my password?" and "I forgot my login credentials" end up with similar vectors, even though they share few words.

This is what makes semantic search possible. Instead of looking for keyword matches, you convert the query to a vector, then find documents whose vectors are closest to the query vector. The assumption is that closeness in vector space correlates with relevance to the query.

That assumption is usually true enough to be useful, but it's not always true, and understanding its limits is crucial.

How embedding models work

Modern embedding models are trained on massive datasets of text pairs that are known to be similar or related. The training process adjusts the model's weights so that related texts produce similar vectors and unrelated texts produce different vectors.

Different models make different tradeoffs. Some are optimized for short queries against longer documents (asymmetric retrieval). Some are trained on specific domains like code or legal text. Some prioritize speed over quality. Some support multiple languages. The model you choose affects what "similarity" means in your system.

The key insight is that the model defines the semantic space. Two texts are "similar" if the model places them near each other. If the model wasn't trained on text like yours, or if your domain uses terminology in unusual ways, the model's notion of similarity might not match what you need.

Similarity metrics

Once you have vectors, you need a way to measure how close they are. The three common metrics are:

Cosine similarity measures the angle between two vectors, ignoring their magnitude. Two vectors pointing in the same direction have cosine similarity of 1, regardless of their length. This is the most common choice for text embeddings because it focuses on the direction of the vector (which captures meaning) rather than its magnitude.

Dot product multiplies corresponding elements and sums them. It's sensitive to both direction and magnitude. For normalized vectors (vectors scaled to length 1), dot product equals cosine similarity. Many embedding models produce normalized vectors, so the choice doesn't matter. If your vectors aren't normalized, dot product will favor longer vectors.

Euclidean distance (L2) measures the straight-line distance between two points. Closer is more similar. Like dot product, it's affected by vector magnitude. For normalized vectors, it's monotonically related to cosine similarity.

In practice, if you're using a standard embedding model with normalized outputs, these metrics give equivalent rankings. Cosine similarity is the conventional choice and what most vector databases default to.

What "semantic" actually means

The term "semantic search" can be misleading. Embeddings capture a particular kind of similarity—one learned from training data—not some Platonic notion of meaning.

Consider a query like "What's the return policy?" The embedding model might find text about "refund procedures" or "exchanges and returns" even without keyword overlap. That's the semantic magic working. But it might also find text about "investment returns" or "the return of the king" because "return" appears in similar contexts across the training data.

Embeddings are good at capturing topic similarity and rough meaning. They're less good at capturing precise logical relationships, negation, or structured facts. "The cat sat on the mat" and "The mat sat on the cat" might have very similar embeddings even though they describe different situations. "Dogs are allowed" and "Dogs are not allowed" might also be similar, because the embedding primarily captures "dogs" and "allowed" rather than the negation.

Understanding these limitations helps you design systems that work around them. If precise matching matters for some queries (product SKUs, error codes, proper nouns), you might need hybrid retrieval that combines embeddings with exact matching.

Choosing an embedding model

The embedding model you choose affects everything downstream. Here are the dimensions that matter:

With Unrag: Supports multiple embedding providers including OpenAI, Cohere, Voyage, and more. See the model selection guide for detailed comparisons.

Start with a mainstream model (OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small, Cohere's embed-v3, or an open-source model like nomic-embed-text) and evaluate on your actual data before optimizing.

The critical rule: match models

The single most important rule for embeddings: use the same model to embed queries that you used to embed documents. Different models produce vectors in different semantic spaces. A query vector from Model A cannot meaningfully be compared to document vectors from Model B—the dimensions don't correspond to the same concepts.

This sounds obvious but causes real problems in practice. Teams change embedding models to get better quality, forget to re-embed their content, and wonder why retrieval stopped working. Or they use one model for batch ingestion and accidentally configure a different model for query time.

If you change embedding models, you must re-embed all your content. There's no shortcut.

When embeddings fail

Embeddings fail in predictable ways. Knowing the failure modes helps you recognize them:

Vocabulary mismatch happens when your users describe things differently than your content does. The documentation says "authentication" but users search for "login." The embedding might bridge some of these gaps, but not all. Query expansion or synonym handling can help.

Domain shift happens when your content uses language differently than the model's training data. Medical, legal, or highly technical content often falls into this category. The model might not understand that terms have specific meanings in your domain.

Precision requirements surface when users need exact matches. If someone searches for error code "E-1234" and you have a document about that error, embedding similarity might not surface it reliably. The embedding captures that it's an error code, but not which specific one.

Short queries often lack enough context for meaningful embedding. "refund" as a query could mean many things. Longer, more specific queries generally retrieve better.

Contradictory or comparative queries like "What's the difference between X and Y?" often retrieve documents about X and documents about Y but not documents that compare them, because the embedding captures the topics but not the comparison structure.

When you encounter these failures, the solution usually isn't a better embedding model—it's designing retrieval strategies that account for the limitations.

Next

With embeddings understood, the next chapter covers chunking: how you split documents into the units that get embedded and retrieved.