Indexing and ANN search

How vector search indexes work and how to tune the recall/latency tradeoff.

Embedding your content produces vectors. Storing those vectors and searching them efficiently requires an index. The choice of index—and how you configure it—determines how fast your searches are and how often they miss relevant results. This chapter explains the tradeoffs so you can make informed decisions for your workload.

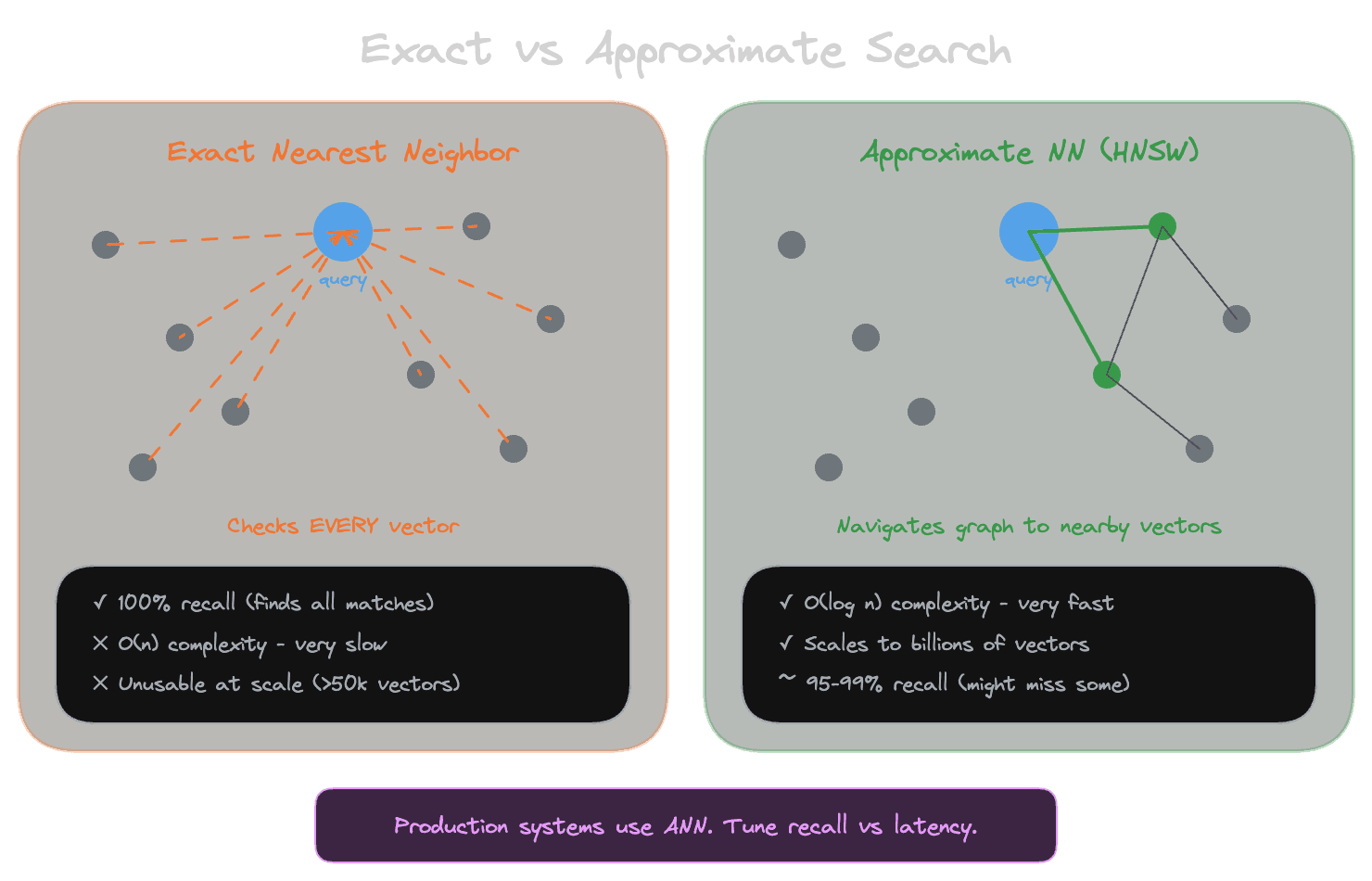

Exact vs approximate search

The simplest way to find the vectors most similar to a query is to compare the query vector to every vector in your index, compute similarity scores, and return the highest-scoring ones. This is exact nearest neighbor search: you're guaranteed to find the actual closest vectors.

Exact search has a problem: it scales linearly with the number of vectors. If you have a million chunks, every query compares against a million vectors. This gets slow as your index grows.

Approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search solves this by building data structures that let you find vectors that are probably among the closest without checking every vector. The tradeoff is that you might miss some relevant results. The vector that's actually closest might not be in the set the algorithm examines.

For small indexes (under 50,000 vectors), exact search is often fast enough and guarantees complete results. For larger indexes, ANN becomes necessary for acceptable latency.

Recall and why it matters

In the context of ANN indexes, recall measures the fraction of true nearest neighbors that the approximate search actually finds. If exact search would return 10 vectors and your ANN search finds 8 of them, your recall is 80%.

Recall matters because the vectors you miss might be the most relevant to the query. If the chunk that perfectly answers the user's question happens to be in the 20% you missed, your RAG system fails even though the content exists in your index.

The relationship between recall and answer quality isn't linear. If you retrieve 10 chunks and only 2 are really relevant, missing one of those 2 is much worse than missing one of the other 8. Low recall on the best matches hurts more than low recall overall.

This is why you shouldn't blindly enable ANN indexes and assume things work. Measure recall on queries that matter to your application. If recall is too low, adjust index parameters or use exact search.

How ANN indexes work

ANN indexes use clever data structures to narrow down the search space. The two most common approaches are:

HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) builds a graph where vectors are nodes and edges connect similar vectors. To find nearest neighbors, you start at a random node and "walk" through the graph toward vectors that are more similar to your query. The hierarchical structure (multiple graph layers with decreasing connectivity) helps navigate large indexes efficiently.

IVF (Inverted File Index) divides the vector space into regions (clusters) and only searches the regions most likely to contain similar vectors. To find nearest neighbors, you first identify which clusters are closest to your query, then search only the vectors in those clusters.

Both approaches trade completeness for speed. You might not explore the region where the best match lives, or your graph walk might not reach it.

Index parameters and tuning

Each index type has parameters that control the recall/latency tradeoff.

For HNSW, the main parameters are m (how many edges each node has) and ef_construction (how many candidates are considered when building the graph). Higher values produce a better-connected graph with higher recall but slower index building and more storage. At query time, ef_search controls how many candidates are considered during the walk. Higher values increase recall at the cost of latency.

For IVF, the main parameter is nlist (how many clusters to create). More clusters mean smaller, more targeted searches but require more overhead to find the right clusters. At query time, nprobe controls how many clusters to search. Higher values search more clusters, increasing recall at the cost of latency.

The right settings depend on your data size, latency budget, and recall requirements. Start with default values, measure recall and latency on representative queries, and adjust. Most systems can achieve 95%+ recall with reasonable latency tuning.

The filtering interaction

When you combine ANN search with metadata filters, the interaction can be tricky. The index structure is built on vectors, not metadata. If you filter out 90% of your vectors based on a tenant ID, the remaining 10% might not be well-connected in the graph, and the ANN algorithm might struggle to find them.

Different databases handle this differently. Some apply the filter after the ANN search (risking too few results). Some scan filtered vectors exhaustively (slow for large filters). Some maintain separate indexes per filter dimension (storage overhead).

If you have highly selective filters (only searching a small fraction of the index), test that filtered queries still achieve acceptable recall. You might need to adjust index parameters or accept exact search for certain filter combinations.

When to use which approach

Exact search makes sense when your index is small (under 50,000 vectors), your latency budget is generous, or recall absolutely cannot be sacrificed. It's simpler and guaranteed correct.

ANN search makes sense when your index is large enough that exact search is too slow. Start with default parameters, measure, and tune. For most applications, 95%+ recall is achievable with sub-100ms latency on indexes of millions of vectors.

Hybrid approaches are also possible. Some systems use ANN for the initial search and fall back to exact search if results seem poor (low scores, too few results). This gives you the speed of ANN most of the time with an escape hatch when it matters.

Next

With indexing understood, the final foundations chapter covers score calibration: how to interpret similarity scores and set meaningful thresholds.