Score calibration and thresholds

Why similarity scores are not probabilities and how to set meaningful thresholds.

When you run a vector search, you get results with scores. It's tempting to treat these scores as confidence levels: "This result scored 0.85, so it's 85% relevant." That intuition is wrong, and acting on it leads to systems that either return irrelevant results or refuse to answer when they should.

This chapter explains what similarity scores actually mean, how to set thresholds that work, and how to handle the case where nothing in your index is actually relevant to the query.

What scores represent

A similarity score measures how close two vectors are in the embedding space. For cosine similarity, the score ranges from -1 to 1, where 1 means the vectors point in exactly the same direction and 0 means they're perpendicular. For distance metrics like L2, lower numbers mean closer vectors.

The score tells you about geometric proximity, not semantic relevance. Two chunks might be close in vector space because they use similar vocabulary, discuss related topics, or were processed by the model in similar ways—not necessarily because one answers a question about the other.

More importantly, scores are not calibrated across different models or even different queries. A score of 0.8 from one embedding model doesn't mean the same thing as 0.8 from another model. A score of 0.8 on a short, specific query doesn't mean the same thing as 0.8 on a long, vague query. The absolute number tells you almost nothing without context.

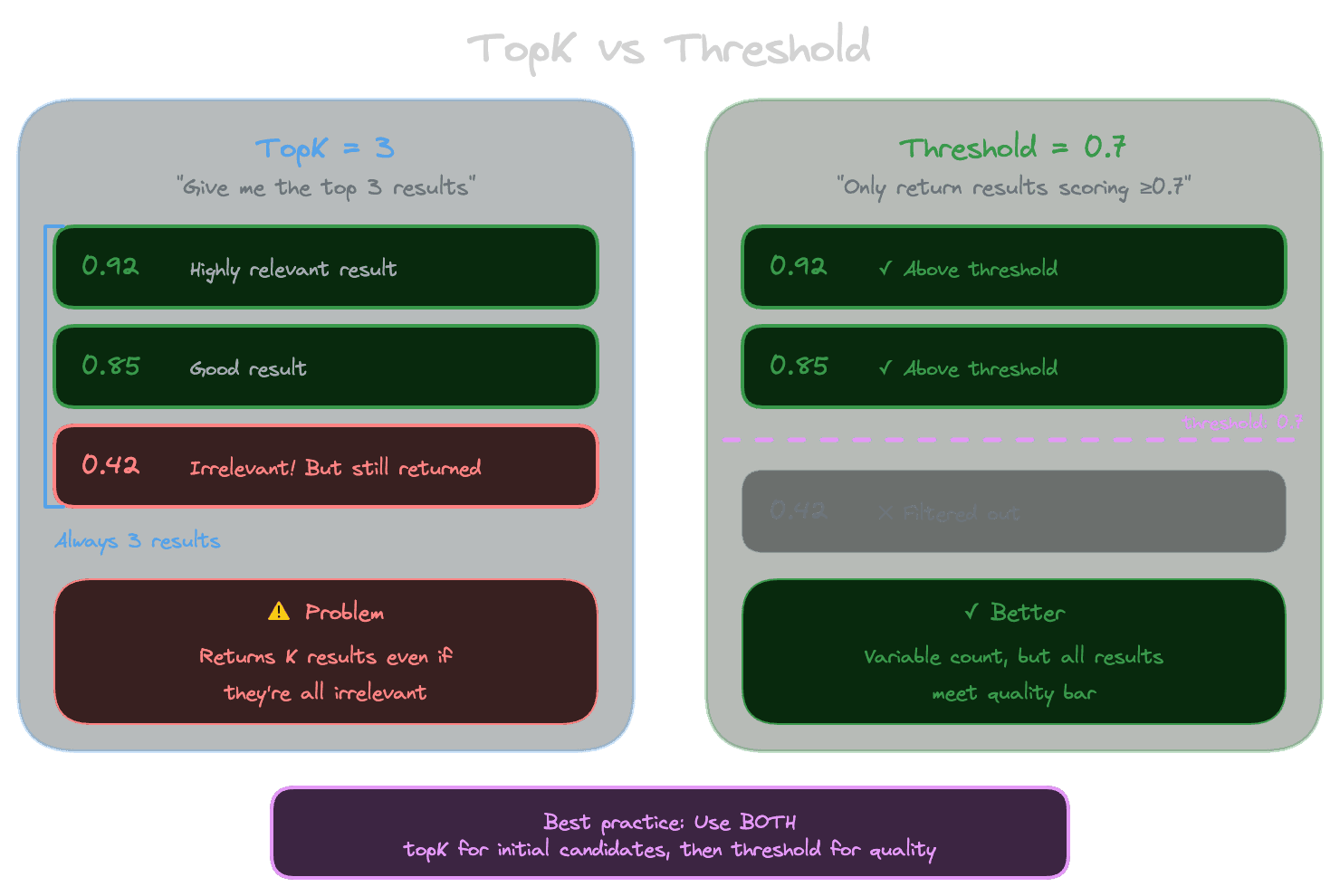

The topK approach

The simplest retrieval strategy ignores scores entirely: just return the top K most similar chunks. Whatever is closest is what you use, regardless of how close "closest" actually is.

This works surprisingly well when you know the index contains relevant content. If a user asks about password reset and you have documentation about password reset, the chunks about that topic will probably be closer to the query than chunks about other topics. TopK gives you the best candidates.

The problem is when the index doesn't contain relevant content. If someone asks about a feature you don't document, topK still returns K results. They'll be whatever is least irrelevant, but they're still irrelevant. The model then generates an answer using context that doesn't answer the question, leading to hallucination or incoherent responses.

Why thresholds help

A threshold provides a minimum quality bar: only return results with scores above a certain level. If nothing scores above the threshold, return no results (or a special "no match" signal). This prevents the system from using irrelevant context just because it's the least-bad option.

Thresholds are tricky because, as noted above, scores don't have absolute meaning. A threshold of 0.7 might be reasonable for one embedding model and one query type but far too high or too low for another combination.

The key is to calibrate thresholds empirically rather than guessing. Run representative queries, look at the results and their scores, and identify a threshold that separates good matches from bad ones. This threshold is specific to your embedding model, your content, and your query patterns.

Combining topK and thresholds

In practice, you usually want both: retrieve up to K results, but only include results above the threshold. This bounds both the number of results (you won't be overwhelmed) and the minimum quality (you won't include irrelevant content).

The typical approach looks like:

- Retrieve top-20 or top-30 results

- Filter to those above the threshold

- Take the top 5-10 of what remains

- If nothing passes the threshold, signal "no good match"

The initial over-retrieval gives you enough candidates that filtering doesn't leave you empty-handed for queries with good matches. The threshold prevents including garbage for queries without good matches.

Calibrating thresholds empirically

To find a good threshold, you need examples of queries with known-relevant results and queries without relevant results.

For queries with relevant results, look at the score distribution. Relevant chunks typically cluster at higher scores. Note the range: are relevant results mostly above 0.7? Above 0.5? This varies by model and domain.

For queries without relevant results (things your knowledge base doesn't cover), look at the best score. If the best match is still 0.6 when you know it's wrong, you know 0.6 isn't a reliable indicator of relevance.

The threshold goes in the gap between these distributions. If relevant results tend to score 0.6-0.9 and irrelevant best matches tend to score 0.3-0.5, a threshold around 0.55 makes sense.

In practice, the distributions overlap: some irrelevant results score higher than some relevant results. You're choosing a tradeoff between false positives (including irrelevant results) and false negatives (excluding relevant results). For most RAG applications, false negatives are better—returning "I don't have information about that" is preferable to returning wrong information.

Per-query-class calibration

Different types of queries behave differently. Short queries like "refund policy" might have different score distributions than long queries like "what's the process for getting a refund if my order was damaged in shipping?" Factual questions behave differently than exploratory questions.

If your application has distinct query classes, consider calibrating thresholds separately for each. This is more work but can significantly improve precision on query types that perform poorly with a global threshold.

At minimum, monitor score distributions over time. If you see a class of queries consistently hitting the threshold (lots of "no match" responses), investigate whether the threshold is wrong or whether the content genuinely doesn't exist.

Handling "no good match"

When nothing passes your threshold, don't force the system to answer anyway. This is where many RAG systems fail: they always pass context to the LLM, even when that context is irrelevant.

Better approaches:

- Return a message like "I couldn't find information about that in my knowledge base."

- Ask clarifying questions to get a query that might match better.

- Suggest related topics that do have coverage.

- Fall back to the model's general knowledge with appropriate caveats.

The right approach depends on your use case. Support assistants should acknowledge gaps. Documentation search can show "no results." Customer-facing products should be helpful without being wrong.

The key insight is that detecting "no good match" is better than pretending you have matches when you don't. Thresholds give you that detection capability.

Next module

With the foundations complete—embeddings, chunking, metadata, indexing, and scoring—you're ready to tackle data and ingestion: how to get content into your RAG system reliably.