Building eval datasets

Curate queries and ground truth that represent real usage without leaking or biasing results.

Evaluation is only as good as your dataset. If your test queries don't represent real usage, your metrics won't predict production quality. If your ground truth is wrong, you'll optimize for the wrong things. Building a good eval dataset is an investment, but it pays dividends every time you make a change and need to know if you broke something.

What goes in an eval dataset

A RAG eval dataset consists of queries paired with expected outcomes.

For retrieval evaluation, each entry needs a query and a list of relevant documents (or passages). This is your ground truth for measuring recall, precision, and ranking metrics.

For answer evaluation, each entry needs a query and an expected answer (or answer criteria). This might be the exact correct answer, key facts that must be present, or a rubric for judging quality.

For end-to-end evaluation, you might combine both: the query, the expected relevant documents, and the expected answer properties.

A practical eval set might have 100-500 examples covering different query types, difficulty levels, and content areas. Larger is better for statistical confidence, but quality matters more than quantity—100 good examples beat 1000 sloppy ones.

With Unrag: The eval battery provides a structured dataset format for defining queries and ground truth, with built-in support for document and passage-level labels.

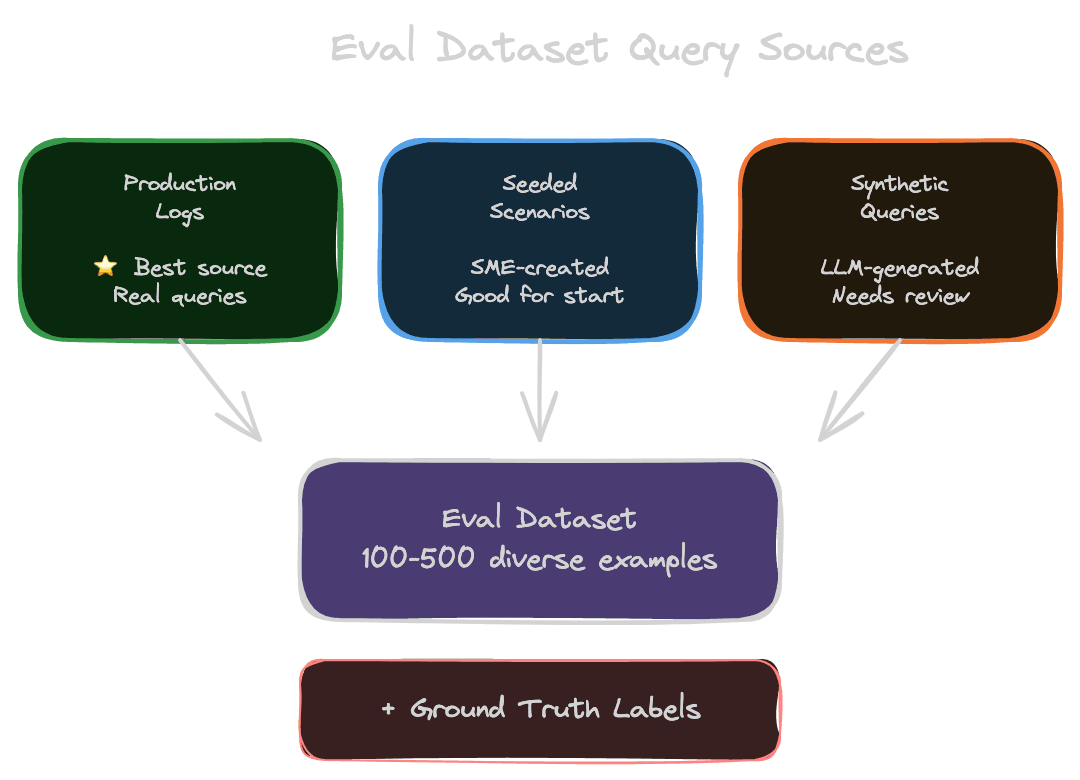

Where to get queries

The best queries come from real usage, but you may not have usage data when starting out.

Production logs are the gold standard if you have them. Real users ask questions you wouldn't think to invent. Sample from logs, filter for quality and diversity, and anonymize if needed. Watch for PII in queries.

Seeded scenarios work when you're starting from scratch. Subject matter experts write queries they expect users to ask. These are useful but tend to be cleaner than real queries—real users are messier and more varied.

Synthetic queries can be generated using an LLM given your documents: "Generate questions that could be answered by this document." This scales well but needs human review to filter bad examples. Synthetic queries often lack the ambiguity and incompleteness of real queries.

Support tickets or search logs from adjacent systems can provide query inspiration even if they weren't asked to your RAG system specifically.

Mix approaches: start with seeded scenarios, add synthetic queries for coverage, then replace with production queries as you get real usage.

Ground truth strategies

Ground truth tells you what the correct outcome is. There are several levels of granularity.

Document-level labels identify which documents are relevant to each query. "For query X, documents A and B contain the answer." This is the minimum for retrieval evaluation.

Passage-level labels are more precise: which specific chunks or sections answer the query. This is better for evaluating chunk-level retrieval but more labor-intensive to create.

Extractive answers specify the exact text span that answers the query. This enables very precise evaluation but requires the answer to be a direct extraction.

Gold answers are the expected full answers. "The correct answer is: 30 days." This enables answer correctness evaluation but requires manual creation for each query.

Answer criteria specify what a good answer must include without providing the exact text. "Answer must mention the 30-day window and the receipt requirement." This is more flexible than exact match but still enables automated checking.

Choose the level of detail based on what you're measuring. Retrieval-only evaluation needs document/passage labels. Answer evaluation needs gold answers or criteria.

Avoiding bias and leakage

Eval datasets can become biased in ways that overstate quality.

Selection bias occurs when test queries are easier than real queries. If your seeded scenarios are straightforward factual questions but real users ask ambiguous, multi-part questions, your eval will overestimate quality.

Label leakage occurs when ground truth leaks into training or tuning. If you tune your chunking strategy to optimize your eval set, you're not measuring generalization—you're overfitting to your test data. Keep a holdout set you never tune on.

Staleness occurs when the eval dataset doesn't reflect current content. If documents change but your ground truth doesn't update, correct answers will be marked wrong.

Coverage gaps occur when the eval dataset only covers certain query types or document types. You might have great metrics on FAQs but miss that technical documentation retrieval is broken.

Regularly audit your eval dataset for these issues. Rotate examples, check for staleness, and ensure coverage across your content and query distribution.

Dataset maintenance

Eval datasets need ongoing maintenance as your system evolves.

Content changes require ground truth updates. When a document is updated, check if any eval queries reference it. When a document is deleted, affected queries need new ground truth or removal.

Distribution shift means the queries users ask change over time. Periodically sample new queries from production and add them to the eval set. Retire queries that no longer represent real usage.

Version control your eval dataset alongside your code. Track changes so you can understand when and why metrics shifted.

Periodic human review catches accumulated errors. Have humans re-verify a sample of ground truth labels regularly. Mistakes compound if left unchecked.

Sizing and statistical power

Small eval sets have high variance. If you have 50 examples and 45 pass, your success rate is 90%—but the confidence interval is wide. A few lucky or unlucky queries can swing your metrics significantly.

For stable metrics, aim for 200+ examples per slice you want to measure. If you want to compare performance on FAQs versus technical docs, you need enough examples of each to measure separately.

When comparing two systems (old versus new), use statistical tests to determine if differences are significant. A 2% improvement on 100 examples might just be noise; on 1000 examples, it's more likely real.

Next

With an eval dataset in hand, the next chapter covers offline evaluation—running tests, establishing baselines, and gating releases on quality.