LLM-as-judge and rubrics

When LLM judges help, when they fail, and how to design rubrics that are stable enough to trust.

Human evaluation is the gold standard for answer quality, but it's slow and expensive. LLM-as-judge uses language models to assess quality automatically, scaling evaluation to thousands of examples. When designed carefully, LLM judges can approximate human judgment at a fraction of the cost. But they have biases and failure modes you need to understand.

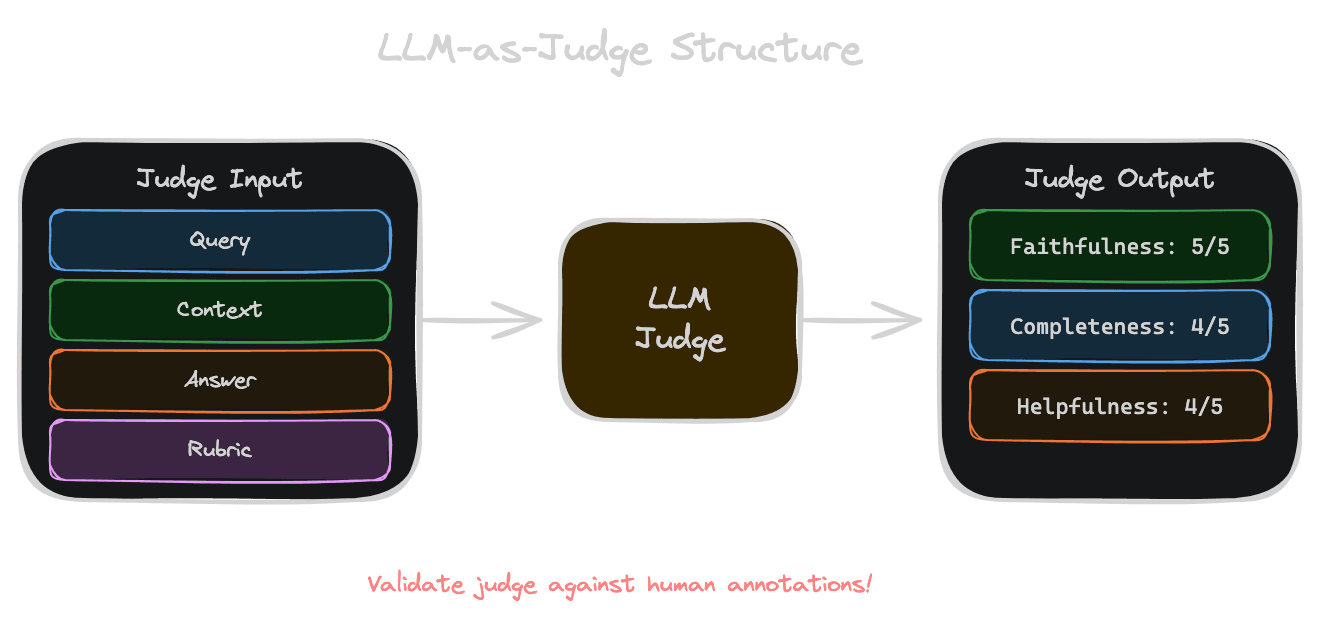

What LLM-as-judge does

You provide the judge model with the query, the context (retrieved sources), the generated answer, and a rubric specifying how to evaluate. The judge outputs a score or judgment on one or more dimensions.

A simple faithfulness judge might be prompted: "Given the context and answer, determine if the answer is fully supported by the context. Score 1 if all claims are supported, 0 if any claim is unsupported."

A more nuanced judge might output multiple scores: faithfulness (1-5), completeness (1-5), and helpfulness (1-5), with explanations for each.

LLM judges enable automated evaluation at scale. You can run them on your entire eval set in minutes, catching issues that would take humans days to review.

When LLM judges work well

LLM judges are effective for certain evaluation tasks.

Faithfulness checking is relatively objective. Given context and answer, determining whether the answer is supported is a task LLMs do reasonably well. The context provides the ground truth, and the judge just needs to verify consistency.

Format compliance is even easier. Does the answer include citations? Is it the right length? Is it structured correctly? These are straightforward checks.

Comparative judgments can be reliable. "Which of these two answers is better?" is often easier for an LLM to judge than absolute quality. Pairwise comparison reduces calibration issues.

Rubric-guided assessment with clear criteria performs better than vague quality judgments. "Does the answer address all parts of the question?" is clearer than "Is this a good answer?"

When LLM judges fail

LLM judges have known failure modes.

Verbosity bias: LLM judges often prefer longer, more elaborate answers even when brief answers are correct. A concise accurate answer might score lower than a verbose meandering one.

Style bias: Judges may prefer answers that sound like their training data (confident, well-structured prose) over answers that are correct but awkwardly phrased.

Sycophancy: Some judges are reluctant to give low scores, producing ratings that cluster toward the positive end. This compresses the score range and makes discrimination harder.

Inconsistency: The same input might get different scores on different runs, especially with non-zero temperature. This adds noise to your evaluation.

Leakage: If the judge has access to information it shouldn't (like the correct answer), it might use that to evaluate, producing overly optimistic results.

Domain blindness: Judges may miss domain-specific errors that a human expert would catch. A factually wrong legal claim might sound plausible to a general-purpose LLM.

Designing good rubrics

A rubric is a structured evaluation guide that tells the judge exactly how to assess quality. Good rubrics reduce ambiguity and improve consistency.

Be specific about criteria. Instead of "Is this answer good?", specify what good means: "Does the answer directly address the question? Does it cite sources? Are the citations accurate? Is it concise?"

Define score levels clearly. If using a 1-5 scale, define what each level means. "5: All claims supported, no hallucinations. 3: Mostly supported with minor unsupported claims. 1: Major unsupported claims or fabrications."

Separate dimensions. Evaluate faithfulness, completeness, and helpfulness separately rather than combining into one overall score. This tells you which aspects are working.

Include examples. Show the judge examples of good and bad answers with their scores. This calibrates expectations.

Use binary judgments when possible. "Is this claim supported: yes/no" is more reliable than "How supported is this claim: 1-5." Aggregate binary judgments for nuanced assessment.

Validating judge quality

Don't trust an LLM judge without validation. Check that it agrees with human judgments.

Collect human annotations on a sample of your eval data. Have humans rate answers on your rubric dimensions. This is your ground truth for validating the judge.

Measure agreement between LLM and human judgments. Cohen's kappa or simple agreement rate tells you how often they agree. If agreement is low, the judge isn't reliable for your task.

Analyze disagreements. When the LLM and humans disagree, who's right? If the LLM is consistently wrong in certain ways, adjust the rubric to address those failure modes.

Check for biases. Does the judge systematically prefer certain answer styles? Test with controlled examples where only irrelevant features (length, style) differ.

Re-validate periodically. As your system and rubrics evolve, judge quality might change. Re-check agreement with humans regularly.

Inter-annotator agreement

Both human annotators and LLM judges have variability. Measure and account for this.

Human-human agreement establishes the ceiling. If humans only agree 80% of the time on a dimension, expecting LLM-human agreement above 80% is unrealistic.

LLM-LLM agreement (same judge, different runs) measures consistency. If the judge gives different scores on repeated runs, it's unreliable. Use temperature=0 and test stability.

Ensemble judges can improve reliability. Have multiple LLMs judge the same example and aggregate (majority vote or average). This reduces noise from any single judge.

Avoiding hidden leakage

Leakage occurs when the judge has access to information that contaminates its judgment.

Don't show the judge the gold-standard answer if you're evaluating whether the generated answer is correct. The judge might say "yes, this matches the expected answer" rather than assessing actual correctness.

Don't show the judge which variant is control vs. treatment in A/B comparisons. Present variants neutrally to avoid bias.

Be careful with chain-of-thought prompting. The judge's reasoning might leak information or assumptions that affect its final judgment.

Next

With automated evaluation via LLM judges, you can assess quality at scale. The final chapter covers using evaluation data to debug—slicing results to find what's actually broken.