Latency budgets and fast paths

Design fast-path and deep-path retrieval flows that respect p95 budgets without sacrificing correctness.

Users expect fast responses. Studies consistently show that latency above a few seconds causes abandonment, frustration, and distrust. But RAG systems are inherently multi-stage—you're chaining network calls to embedding services, vector databases, rerankers, and LLMs. Each stage adds latency. Without deliberate design, it's easy to end up with end-to-end latencies that feel sluggish.

The solution isn't to make every component as fast as possible. That's often impossible or prohibitively expensive. Instead, you budget latency across stages, design fast paths for common cases, and accept that some queries will take longer if they need deeper processing. The goal is making typical queries fast while keeping hard queries correct, even if slow.

Setting a latency budget

Start by deciding your target end-to-end latency. This should be driven by user experience, not by what's technically convenient. For conversational interfaces, 1-2 seconds to first token feels responsive. For search interfaces where users expect near-instant results, you might need sub-second total latency. For batch processing, latency matters less than throughput.

Once you have a target, decompose it across stages. A typical RAG request might allocate 50-100ms for query embedding, 50-200ms for retrieval, 100-300ms for reranking (if used), and the remainder for generation. These aren't hard limits—they're budgets that help you identify which stages need optimization.

When any stage exceeds its budget, you have a decision: optimize that stage, reduce its scope (fewer candidates, simpler model), or accept the latency hit. This framing forces explicit tradeoffs rather than hoping everything magically stays fast.

The fast path

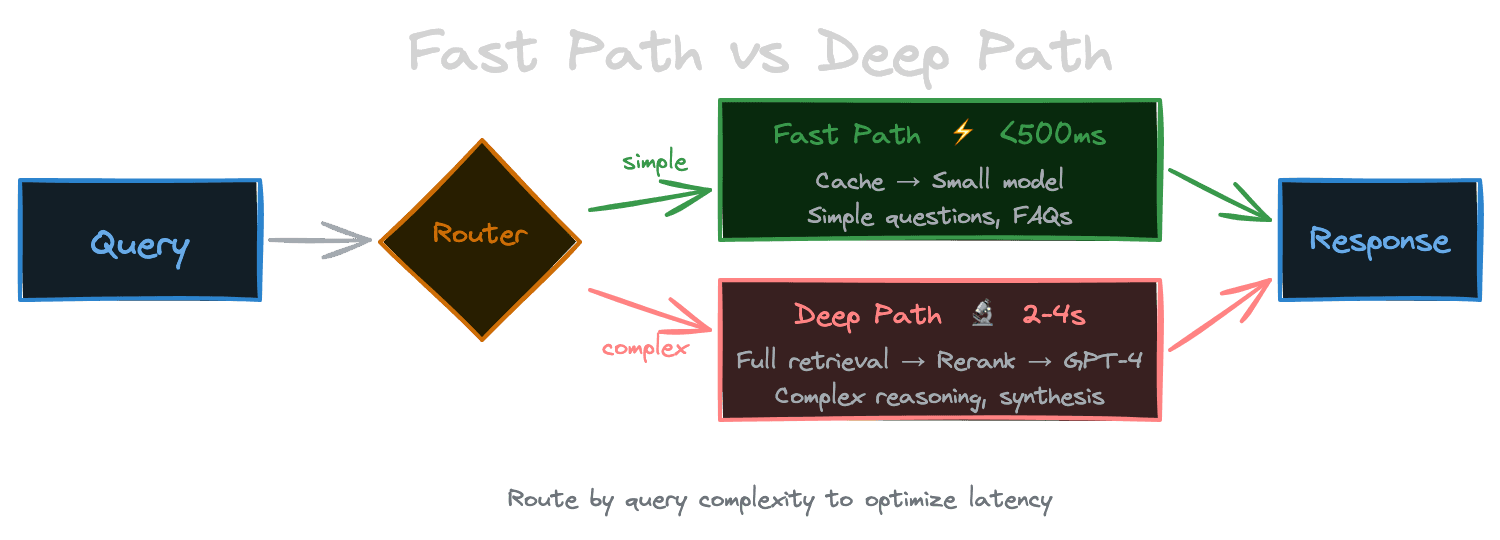

Most systems benefit from a fast path: a lightweight processing route for queries that can be answered quickly. The fast path might skip expensive stages, use simpler models, or cache aggressively.

Consider a support chatbot. Common questions—"how do I reset my password?" or "what are your business hours?"—are asked frequently and have well-known answers. The fast path might check a cache of recent query embeddings, retrieve from a hot index of popular content, skip reranking entirely, and use a faster (if less capable) generation model. For these queries, latency can be under a second.

Less common or more complex queries take the deep path: full retrieval, reranking, and powerful generation. Latency might be 3-4 seconds, but these queries genuinely need the extra processing.

The key is detecting which path a query should take. Simple heuristics work: query length, presence of technical terminology, cache hit rates. More sophisticated routing uses a classifier or the retrieval scores themselves—if the top-k similarity is above a threshold, the fast path is probably sufficient.

Time-to-first-token and streaming

For generation-heavy latencies, time-to-first-token (TTFT) matters as much as total latency. Users perceive streaming responses as faster even when total latency is the same, because they see activity immediately and can start reading while generation continues.

Optimize for TTFT by starting generation as soon as context is ready, not waiting for final post-processing. Stream tokens to the client as they're generated. If you're aggregating from multiple retrievers or doing parallel processing, consider streaming partial results.

This is especially impactful for longer responses. A 500-token response at 50 tokens/second takes 10 seconds total, but if TTFT is 500ms, users see the answer starting almost immediately and don't perceive the full 10 seconds as latency.

Progressive enhancement

Some systems benefit from progressive enhancement: return an initial fast answer, then refine it with deeper processing.

For a search interface, this might mean showing vector search results immediately, then re-sorting them after reranking completes. For a generation interface, it might mean streaming an initial answer from a fast path while a slower path validates or enhances it.

Progressive enhancement works when the fast answer is usually correct. If the deep path frequently reverses the fast path's answer, users get confused by the changing response. But if the deep path only improves on the fast path—adding nuance, fixing minor issues—progressive enhancement gives both speed and quality.

Parallel versus sequential processing

Latency compounds when stages are sequential. If you have three 100ms stages, total latency is 300ms. But if you can parallelize stages, latency improves dramatically.

Look for parallelization opportunities in your pipeline. If you're querying multiple indexes, query them in parallel. If you're doing query expansion into multiple sub-queries, embed them in parallel. If retrieval and context preparation can overlap, start preparing templates while retrieval runs.

Be mindful of dependencies. You can't rerank before retrieval. You can't generate before context is assembled. But within stages, parallelism often exists. Batching multiple embedding requests into a single API call is a form of parallelism that reduces per-request overhead.

Latency versus quality tradeoffs

Faster options typically sacrifice quality. A smaller embedding model embeds faster but may retrieve less accurately. Fewer candidates retrieve faster but might miss relevant documents. A smaller LLM generates faster but might produce worse answers.

Make these tradeoffs explicit. For your fast path, quantify how much quality you sacrifice for the speed gain. If the fast path has 5% lower recall but 3x faster latency, that's a reasonable tradeoff for common queries. If it has 20% lower faithfulness, that might not be acceptable.

Use your evaluation framework (from Module 7) to measure quality at different latency points. Build dashboards that show quality metrics alongside latency, so degradations in either are visible together.

Adaptive timeouts and early exit

When a stage is taking too long, should you wait or bail out?

Adaptive timeouts let you set a maximum time for any stage, returning whatever results are available when the timeout fires. For retrieval, this might mean returning fewer results than requested. For reranking, it might mean returning unranked candidates. For generation, it might mean truncating the response.

Early exit is similar but based on confidence rather than time. If retrieval returns highly confident results quickly, you might skip reranking entirely. If the first few generated sentences seem complete, you might stop generation early.

These strategies require graceful degradation. A partial response should still be useful, even if not optimal. Design your system so each stage's output is meaningful even if subsequent stages are skipped.

Caching for latency

Caching is often the single biggest latency win.

Cache query embeddings so repeated or similar queries skip embedding entirely. Cache retrieval results so identical queries (with the same filters) return instantly. Consider semantic caching that matches queries by embedding similarity, not just exact match.

Be thoughtful about cache invalidation. Embedding caches rarely need invalidation (the embedding model doesn't change often). Retrieval caches need invalidation when the underlying corpus changes—a document added or removed should invalidate relevant cache entries.

For generation, caching is trickier. Identical queries with identical context can be cached, but context often varies slightly. Some systems cache at the passage level (this passage generates this summary) rather than the full response level.

Next

With latency under control, the next chapter covers cost—the other operational constraint that shapes production RAG systems.