Reliability: fallbacks and degraded modes

Design for partial failure - missing embeddings, slow databases, rate limits, and safe answers.

Production systems fail. Network connections drop. APIs hit rate limits. Databases slow down under load. Models return errors. The question isn't whether your RAG system will experience failures, but how it will behave when they happen. A well-designed system degrades gracefully: it continues providing value—perhaps reduced—rather than failing completely.

Reliability engineering for RAG is about identifying failure modes at each stage and deciding in advance what to do about them. Some failures can be retried. Some can be worked around. Some require returning a degraded response. And some genuinely require telling the user that the system is unavailable.

Failure modes across the pipeline

Each stage of your RAG pipeline can fail in different ways.

Embedding might fail due to model service unavailability, rate limiting, or timeout. If you can't embed the query, you can't do vector retrieval. The impact is severe—no embedding means no retrieval.

Retrieval might fail due to database downtime, network issues, or slow queries. Even partial failures are possible: the database might be up but return incomplete results, or queries might timeout while returning partial data.

Reranking might fail if your reranker service is down or rate limited. This is often a third-party API call, making it a common failure point.

Generation might fail due to LLM provider outages, rate limits, content filtering, or timeout. LLM APIs are generally reliable but not perfect, and rate limits are common during traffic spikes.

Additionally, your corpus itself might have problems. Missing documents, corrupted embeddings, or stale data can cause failures even when all services are healthy.

Timeout strategy

Timeouts are your first line of defense against slow failures. Without timeouts, a hung connection can block resources indefinitely.

Set timeouts for every external call: embedding, retrieval, reranking, generation. Make them appropriate to the operation. Embedding is usually fast (100-500ms); if it takes 5 seconds, something is wrong. Retrieval might be fast or slow depending on your index; set a timeout that accommodates normal p99 latency plus margin. Generation can legitimately take several seconds for long responses.

When a timeout fires, you have a decision: retry, fallback, or fail. The answer depends on the stage and the cause. A one-time network hiccup might justify a retry. Persistent slowness suggests the service is overloaded and retries will make it worse.

Retry policies

Retries can recover from transient failures but can also amplify problems if done carelessly.

Retry with backoff spaces out retries to avoid hammering a struggling service. Exponential backoff (wait 100ms, then 200ms, then 400ms) is standard. Add jitter to prevent thundering herd when many clients retry simultaneously.

Limit retry attempts to avoid infinite loops. Two or three retries is usually enough. If the operation fails repeatedly, something is genuinely wrong.

Don't retry everything. Some failures are not transient: a 404 for a missing document won't resolve with retry. Rate limit errors might require longer backoff. Content filtering rejections won't change on retry.

Retry budgets limit the total retry load on the system. If more than X% of requests are retrying, the system is in trouble—additional retries will make it worse. A retry budget can disable retries when the system is overloaded.

Circuit breakers

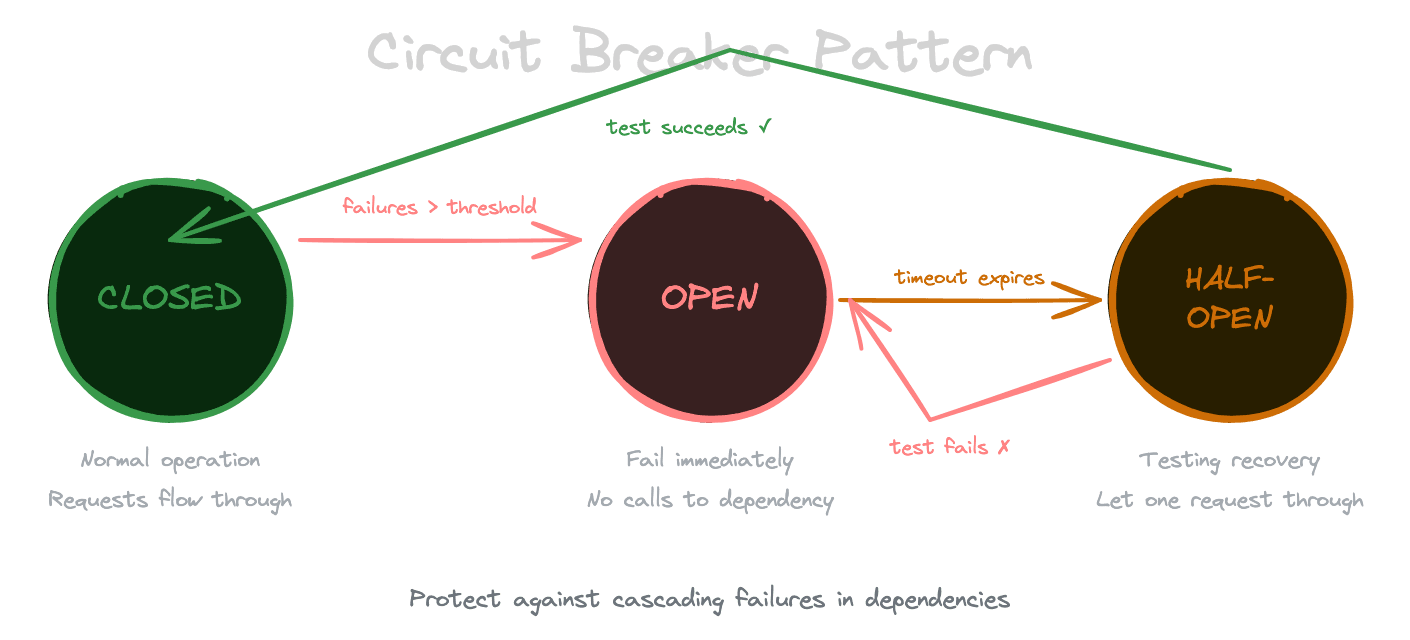

When a dependency is failing persistently, you want to stop calling it—both to avoid wasting resources and to give it time to recover. This is the circuit breaker pattern.

A circuit breaker tracks failure rates for a dependency. When failures exceed a threshold, the circuit "opens" and immediately fails subsequent calls without actually making them. After a cooling-off period, the circuit "half-opens" and allows a test call through. If the test succeeds, the circuit closes and normal operation resumes. If it fails, the circuit reopens.

Apply circuit breakers to your LLM provider, reranker service, and any other external dependencies. When the circuit is open, trigger your fallback behavior rather than waiting for failures.

Fallback strategies

When a stage fails, what's the fallback?

Embedding fallback: If your primary embedding model is unavailable, you might fail open (no results), fail closed (return a canned error), or use a cached embedding. Some systems maintain a fallback embedding model, though this requires careful testing since results will differ.

Retrieval fallback: If vector retrieval fails, you might fall back to keyword search (BM25) if you have that capability. You might return results from a stale cache, acknowledging they might not be current. Or you might return an empty result and let generation handle it.

Reranking fallback: If the reranker fails, return retrieval results without reranking. You've lost precision, but results are still usable. This is one of the easier fallbacks to implement.

Generation fallback: If the primary LLM fails, you might route to a backup provider, fall back to a smaller model, or return a templated response that incorporates retrieved content without LLM synthesis. Some systems cache common responses and return cached answers when generation fails.

Degraded mode design

Degraded modes give users partial functionality rather than complete failure. Design them deliberately, not accidentally.

No retrieval mode: If retrieval is down, can your system answer from the LLM's parametric knowledge? This is risky for knowledge-heavy applications (the answers might be wrong or outdated), but for some queries it's better than nothing. Be transparent: "I'm answering from my general knowledge because the documentation is temporarily unavailable."

No generation mode: If generation is down, can you return raw retrieval results? For search-style interfaces, this might be acceptable. Users see the relevant documents and can read them directly.

Cached-only mode: If you can serve from caches but not from live services, you can handle repeated queries while new queries fail. This works well for systems with high query repetition.

Design these modes upfront and test them. Know what your system does when each component is unavailable. Document it so your team isn't surprised during an incident.

Graceful user experience

How you communicate failures affects user perception as much as the technical response.

Be transparent. If results are incomplete or degraded, say so. "I found some relevant information, but the service is experiencing issues—results may not be complete." Users tolerate degraded service better when informed.

Suggest alternatives. If the system can't help, can it direct users elsewhere? "I'm unable to search the documentation right now. You might try the help center directly at..."

Avoid generic errors. "Something went wrong" is frustrating. "The search service is temporarily unavailable" is informative. If you can estimate recovery time, share it.

Track degraded experience. Monitor how often users encounter degraded modes. If it's frequent, you have a reliability problem to fix. If it's rare but handled gracefully, your investment in fallbacks is paying off.

Testing failure modes

You can't rely on production incidents to verify your fallback behavior. Test failures deliberately.

Chaos engineering involves intentionally injecting failures in test or staging environments. Block network access to your embedding service and verify the system handles it. Inject timeouts in retrieval. Return errors from generation.

Load testing reveals failures that don't appear at low volume. Your system might work fine with 10 QPS but start timing out at 100 QPS. Load test each stage to find breaking points.

Dependency simulation with mock services lets you test specific failure scenarios. A mock that returns 503 errors lets you verify circuit breaker behavior without breaking real dependencies.

Next

With reliability covered, the next chapter addresses governance, privacy, and compliance—constraints that production RAG systems must respect.