Scaling and multi-tenancy

Isolation models, sharding strategies, and operational patterns for large multi-tenant deployments.

The RAG system that works for one user, one corpus, and ten queries per minute faces different challenges than one serving thousands of tenants with millions of documents and thousands of queries per second. Scaling introduces problems that don't exist at small scale: tenant isolation, noisy neighbors, index management, and operational complexity. Multi-tenancy adds questions about data separation, performance fairness, and cost allocation.

This chapter covers strategies for scaling RAG systems and handling multi-tenancy—the patterns that let a single system serve many distinct users or organizations safely and efficiently.

Tenant isolation models

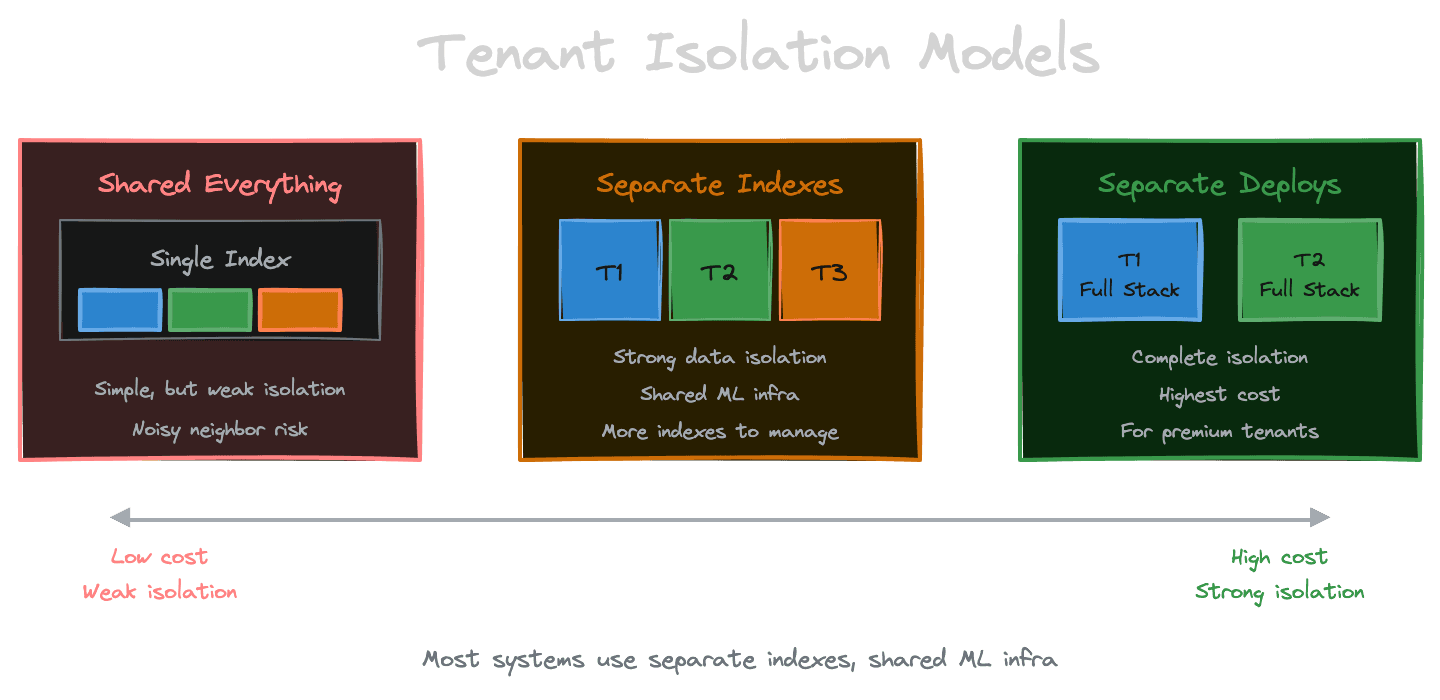

When multiple tenants share a RAG system, you need to decide how strongly to isolate them. The spectrum runs from fully shared to fully isolated, with tradeoffs at each point.

Shared everything puts all tenants' content in one index, distinguished by metadata. Queries filter by tenant ID. This is operationally simple—one index to manage—but provides weak isolation. A bug or misconfiguration could expose one tenant's data to another. Performance is shared; a large tenant can slow down small ones.

Shared infrastructure, separate indexes gives each tenant their own vector index while sharing the embedding, reranking, and generation infrastructure. Isolation is stronger—tenants can't accidentally see each other's data because their indexes are separate. But you're managing many indexes, which has operational overhead.

Separate deployments gives each tenant their own complete stack. Isolation is complete, but so is the cost. This only makes sense for a few large tenants, not hundreds or thousands of small ones.

Most systems end up with separate indexes per tenant, shared infrastructure for the expensive ML components. This balances isolation with efficiency.

Metadata-based tenant isolation

The shared-everything model uses metadata filtering to isolate tenants. Every chunk is tagged with a tenant ID, and every query includes a filter on that ID.

This works, but requires discipline. Every ingestion must set the tenant ID correctly. Every query must include the filter. A single bug—a missing filter, a wrong tenant ID—can expose data. Treat tenant isolation as a critical security property, not just a convenience.

Some vector databases support row-level security or similar features that enforce tenant isolation at the database layer, making it harder to accidentally bypass. If your database supports this, use it. Defense in depth applies.

Performance can be affected by large indexes with many tenants. The database must evaluate the filter across all records, which might be slower than querying a smaller, dedicated index. Monitor query latency as you add tenants; you may need to shard or switch to separate indexes.

Index sharding strategies

As your index grows—more documents, more tenants, more embeddings—a single index may not be sufficient. Sharding splits the index across multiple nodes or partitions.

Sharding by tenant puts each tenant's data on a separate shard. This naturally isolates tenants and allows you to place large tenants on more powerful hardware. Queries only hit the relevant shard.

Sharding by corpus type splits different content types. Documentation might be on one shard, support tickets on another. Queries can target the relevant shard based on intent.

Sharding by time is useful for time-sensitive data. Recent data goes on hot shards optimized for fast access; older data goes on cold shards that might be slower. This requires routing queries to the right shards based on time ranges.

Hash-based sharding distributes data randomly across shards based on document ID. This balances load but requires querying all shards for any query, then merging results. It's simple but has higher query costs.

The right sharding strategy depends on your access patterns. Tenant-based sharding works well when queries are always scoped to one tenant. Content-based sharding works when queries target specific content types. Choose based on how your queries are actually structured.

Handling noisy neighbors

In a shared system, one tenant's behavior can affect others. A tenant with a massive corpus might slow down index updates. A tenant with extremely high query volume might consume disproportionate resources. This is the noisy neighbor problem.

Resource quotas limit what any single tenant can consume. Cap the number of documents per tenant, the number of queries per time period, the maximum query complexity. Enforce these limits at the application layer.

Rate limiting specifically targets query volume. If a tenant exceeds their query-per-second allocation, requests are delayed or rejected. This prevents one tenant from monopolizing query capacity.

Isolated compute for critical tenants ensures that important customers aren't affected by noisy neighbors. You might run premium tenants on dedicated infrastructure while smaller tenants share resources.

Monitoring by tenant lets you see who's consuming resources. Dashboards should show query volume, latency, and error rates per tenant. When problems occur, you can quickly identify if a specific tenant is the cause.

Scaling ingestion

Ingestion at scale—millions of documents, continuous updates—requires different patterns than small-corpus ingestion.

Batch ingestion processes documents in bulk, typically during off-peak hours. It's efficient for initial loads and periodic refreshes. Batch jobs can parallelize heavily and make efficient use of embedding batch APIs.

Streaming ingestion processes documents as they arrive, keeping the index fresh. This requires durable queues (to handle spikes), idempotent processing (to handle retries), and efficient update mechanisms.

Parallelization is key to ingestion throughput. Embedding is often the bottleneck; parallelize embedding requests to the extent your provider allows. Document extraction and chunking can run in parallel workers.

Incremental updates avoid reprocessing unchanged content. Hash documents and skip those that haven't changed. This dramatically reduces ingestion cost for corpora that update frequently but incrementally.

Scaling retrieval

Query load scales differently than ingestion load. Retrieval must be fast and consistent even under high concurrency.

Read replicas let you scale query capacity by adding more index nodes. Queries are distributed across replicas; ingestion goes to the primary and replicates outward. This is standard database scaling but applies to vector stores too.

Caching reduces load on the index. Query embeddings can be cached (exact or semantic). Retrieval results can be cached for repeated queries. Hot content that's retrieved frequently can be cached at the application layer.

Query routing directs queries to appropriate shards or replicas based on load, latency, or content. Smart routing can improve average latency by avoiding overloaded nodes.

Cost allocation for multi-tenancy

When tenants share infrastructure, how do you allocate costs?

Per-query pricing charges tenants based on their query volume. This is simple and correlates roughly with resource consumption. But it doesn't account for query complexity—a query over a million-document corpus consumes more resources than one over a thousand documents.

Tiered pricing offers different plans with different limits (documents, queries, features). This is easy for tenants to understand but may not perfectly match resource consumption.

Resource-based pricing measures actual resource consumption—storage, compute time, tokens processed—and charges accordingly. This is accurate but complex to implement and harder for tenants to predict.

Hybrid models combine approaches: base fee plus usage charges, tiered plans with overage fees.

Whatever model you choose, instrument your system to track consumption by tenant. Even if you don't charge back immediately, you need the data to understand your unit economics and identify outliers.

Operational complexity

Multi-tenant systems are operationally complex. Embrace automation and observability to manage this complexity.

Provisioning automation creates new tenant resources (indexes, metadata, configurations) without manual intervention. A new tenant should be onboarded through self-service or API, not through tickets and manual work.

Deployment automation rolls out updates safely across many tenants. Consider canary deployments that affect a few tenants first, expanding to all tenants after validation. Tenant-specific rollbacks let you revert for one tenant without affecting others.

Monitoring at scale aggregates metrics across tenants while allowing drill-down to individual tenants. Dashboards should show system-wide health and allow filtering to specific tenants.

Incident management considers tenant impact. When something breaks, which tenants are affected? Can you communicate proactively with them? Does your status page show tenant-specific information?

Conclusion

Scaling and multi-tenancy transform RAG from a project into a product. The patterns in this chapter—isolation models, sharding strategies, quota management, operational automation—are what separate prototypes from production systems that serve many users reliably.

This also concludes Module 8. You now have a foundation for operating RAG systems in production: observability to see what's happening, latency and cost controls to keep the system sustainable, security defenses against the unique threats RAG faces, reliability patterns for graceful degradation, governance to meet compliance requirements, and scaling strategies for growth.